Everyone is a Narcissist Together

Robin Tim Weis

The bathhouse is a constitutional right for us humans, speaking to our newly acquired free time, which transcends the historical notion of time as productivity.

Introduction

The 2040 utopian story “Everyone is a Narcissist Together” deals with the urge to highlight how we can step out of an equilibrium in which we are either entrapped at work or trapped on our devices at home. Our entire bandwidth of existence seems to be monetized. We may enjoy ever higher productivity rates, yet, our social infrastructure is in decline as we retreat and give up on devising meaningful ways in how we can and should spend our free time. Rapid advancements in AI and machine learning make the 15-hour work week once anticipated by John Maynard Keynes in his Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren manifesto seem feasible. The answer in 2040 thus lies in a practice deeply rooted in history—visiting bathhouses.

Throughout human history, communities from all around the world congregated around bathhouses. The draw was a simple yet effective one. Come to this forum, meet those you would otherwise not meet, cleanse yourself, and forget about class, cloth, or clout for a few fleeting hours. Bathing is truly a prelude to embracing narcissism in its natural form, stripped of any digital interface, bathhouses allow people to demonetize narcissism’s media value. In 2040, the bathhouse is a constitutional right for humans, speaking to our newly acquired free time, which transcends the historical notion of time as productivity. The time of the now is zero time, that is, the negation of the real time of production. We are free. We are clean. We are all enjoying revolutionary play. Everyone is a narcissist together.

This 2040 utopia deliberately decided to take a measured, incremental storytelling approach. It is not immediately identifiable; instead, it develops and tests itself in the skepticism of its characters.

Keywords

About the author

Robin Tim Weis

Office of Science and Technology Austria (OSTA)

The peanut was a relentless enemy. Fickle, stubborn, and illusive to Ilan’s chopsticks, which were coated in a bright, almost fluorescent, tamarind glow. He flung the chopsticks aside and decided to pinch the last peanut with his fingers instead, devouring his salty conquest. Once he had wiped away all the evidence, Ilan discarded his leftover pad thai breakfast and quickly switched on his TV, just in time to catch the opening remarks.

“All rise, the European Court of Human Rights is now in session. We gather today with this draft protocol in question that resulted from of a lengthy process culminating in the Wassenaar Declaration.

Much has been contested on this issue, and we, as the European Court of Human Rights, are called to action now in 2040 to rule over the constitutional nature of …”

Sarah twirled the loose linen in her hands, inspecting it with the accuracy one would use to survey cracked eggs that had not survived the trip from the grocery store. Was this going to hold up in her weekly ritual? With skepticism, she decided to buy three meters of fabric. She would later sew on patches at home. One was drenched in bold burgundy colors and resembled the silhouette of a wine glass. The other patch had five distinctive spheres in various colors that made for a very gay version of a Medici insignia. She definitely felt royal in her new robes, despite the rough seam. It was only her fourth attempt to date at sewing garments, which represented a novel achievement for her in a time of 3D printers and mobile garment factories that had started to litter even her hometown, the picturesque hamlet of Leimen, Germany. Satisfied with her thin linen robes and sewing, she packed them into her tote bag and walked over to her bus stop.

The bus ride was smooth, punctual, identical in route and in acceleration. Sarah was often annoyed by the mundanity of the bus ride. Autonomous buses never suddenly jerked or swerved to the right, tumbling all the passengers to the side like a cheap, out-of-sync washing machine. She remembered being tossed around like a bag of potatoes as a child on conventional combustion engine buses. Oh, what she would have given for a good tumble, a nice jerk, followed by a deft thump of the head against the reinforced glass. You know a sudden stop, something abrupt that left you with a bruise, maybe, even a scar. But, alas, this was her home, and this was her bus, all automated, as it had been for decades.

At first, the regional bus line had experienced some hiccups. Several buses had ended up driving into the ditch down by the former American army base. The AI-equipped bus and its sensors had kept failing under the relentless glare of the evening sun. It had made for funny headlines but had not stopped the advent of digitization. Everyone was sold on cheap, affordable buses that never stopped or took scheduled breaks and, of course, did not require grumpy drivers. Much like her favorite Flips peanut chips, combustion engine buses first disappeared from view and then vanished from the aisles of consumer choice. They became relics, museum pieces, much like the DVDs Sarah had once found in the attic of her grandparents’ house.

Her grandparents’ DVD collection had made for amusing viewing parties. How monolithic the early 2000s had been! Crowds had flocked into department stores like hens. These chicken coops of retail had stocked their inventory with the products of exploited workers from faraway places like Bangladesh or Thailand. But the big fire of 2035 in Pyongyang, North Korea, had changed the dynamics of the garment industry. After the economic liberation of North Korea in the early months of 2030, garment factories had popped up like mushrooms in the Stalinist outpost. What had followed next was a common tale of capitalistic outsourcing. Bangladeshi, Vietnamese, Burmese, and Thai subcontractors had passed on the buck, and North Korea had ended up bearing the exploitative brunt of the insatiable fashion industry. When 35 adjacent factories all burned down in 2035, the consumers of the industrialized world had decided to fundamentally alter the means of production and logistics of the fashion industry. What had followed was a blitz-like scale-up of 3D-printing microfactories, which spread like the ill-advised fashion trend of Hawaiian shirts in 2036. H&M, Zara, and their Chinese counterpart Orchily were now in the business of command-p fashion. Hyperlocal fashion trends were printed instantaneously and released to the market within hours instead of months. The idea of a fall collection was banal. Fashion was now a morning or afternoon affair in most towns. Subsequently, clothes were discarded from closets at a much faster pace as well. It was only due to the advent of the circular economy model in the state of Baden-Württemberg that this reckless attack of attire had survived to date. The recycling plants hummed away 24 hours a day in order to keep up with the demand for discarded clothing.

Sarah stared into the distance, her wide-open mouth speaking volumes of how bored and lonely she was. To pass time, she conducted what felt like try 348 of the never-ending saga of trying to trust technology. She took out her phone, switched it to video mode, captured her physical profile, and entered her metrics. Once her quick selfie video scan was done, the heavenly father almighty artificial intelligence worked away and came back in five seconds with a suggestion that turquoise really suited her freckled ginger face. She disagreed, and did not end up sending in her turquoise jumpsuit order, which would have been printed and ready for pick-up within the hour. The sheer proximity of both physical and digital technology to her home made her sick. She didn’t want all the trends of this world to be printed three minutes away from her house, especially in the former shed that had belonged to her uncle several decades ago. Once, she had shotput moldy timber off the roof of that shed. She had even lost her virginity on its rickety wooden floor to Rainer Fühlwerk. How ironic it was that the shed had been colonized for good by black-box technologies that were no better at guessing and knowing what she wanted than Rainer had back then.

AI had given the decrepit shed a new life, but it was a life Sarah did not want and had never asked for. The big fallacy of her generation was to continue the idiocy of wanting everything in an instant and at the proverbial tap of a button. Her peers had ruined self-care and opened up the gates of metropolitan brutality to the countryside. But enough of her ramblings: Sarah Idon stepped off that damn magic school bus and morphed into Gabriele Meduci, her confident alter ego, whose feet just hit the pavement.

Sarah Idon and Gabriele Meduci were the same age, and were even from the same corner of Baden-Württemberg; they could have passed for sisters if they’d been two distinctive people. Gabriele was a true and free spirit, a chirpy robin bird in a sea of grey dull Sarah pigeons. She had never received any form of formal education, unlike Sarah. Instead, Gabriele had retreated into the bushy Black Forest not far away from Heidelberg. It was here that she had learned to craft fainting chairs out of entire tree trunks. It had taken her three years to master this craft. Now, she was selling her fainting chairs near and far. The chairs were so surreptitiously smooth, soft and polished that most customers did not even end up purchasing additional pillows to pad the chairs. Gabriele truly lived a holistic and distant life. When she walked out of the bus and across the grass field, she barely left footprints.

When Gabriele saw Ilan, she waved the two new linen robes towards him like a Matador. He seemed unfazed by the new attire at first. Instead, he was more interested in his newly acquired tactile free time. He proclaimed; “Work-free Wednesday’s! Who would have ever worked the entire week in the past?” Ilan had a point; nobody in his circle of friends knew anyone who worked three, let alone four, days a week. The benchmark of a 40 hours workweek seemed absurd to him. The entire concept of slaving away five or more days a week was archaic to them both. Automation had really disembarrassed itself from the manual toiling of past generations and “took wings into the future”[1] as John Maynard Keynes had once foreseen in his Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren manifesto. Both Ilan and Gabriele worked hours reminiscent of the 15 hours Keynes had anticipated.

“Wait Gabriele! Before we go inside, I want to quickly check THE court ruling on the right to unemployment.” Ilan could not contain his excitement and whipped out his phone. Gabriele was annoyed; Sarah would have probably just rolled her eyes and saved her energy for another confrontation.

“As a just and free European Union, we need to hold evident that our societies must evolve and reflect their social fabric and state. In this respect, the European Court of Human Rights can no longer overlook the damning evidence that gainful employment has been replaced in large by autonomous machines and programs. We therefore, hereby, rule in favor of the European Right to Unemployment and Meaningful Activity.”

CC-BY-SA 2.0 Ivan Chopyk

Both Ilan and Gabriele were elated. What they had long practiced was now accepted, enshrined in law, written and ruled, codified for eternity. For them, this was less of a watershed moment, but rather a long overdue conclusion. Even though they still worked two days a week, they now had the right to pursue their true interests and, more importantly, they would not have to pay for their favorite pastime moving forward.

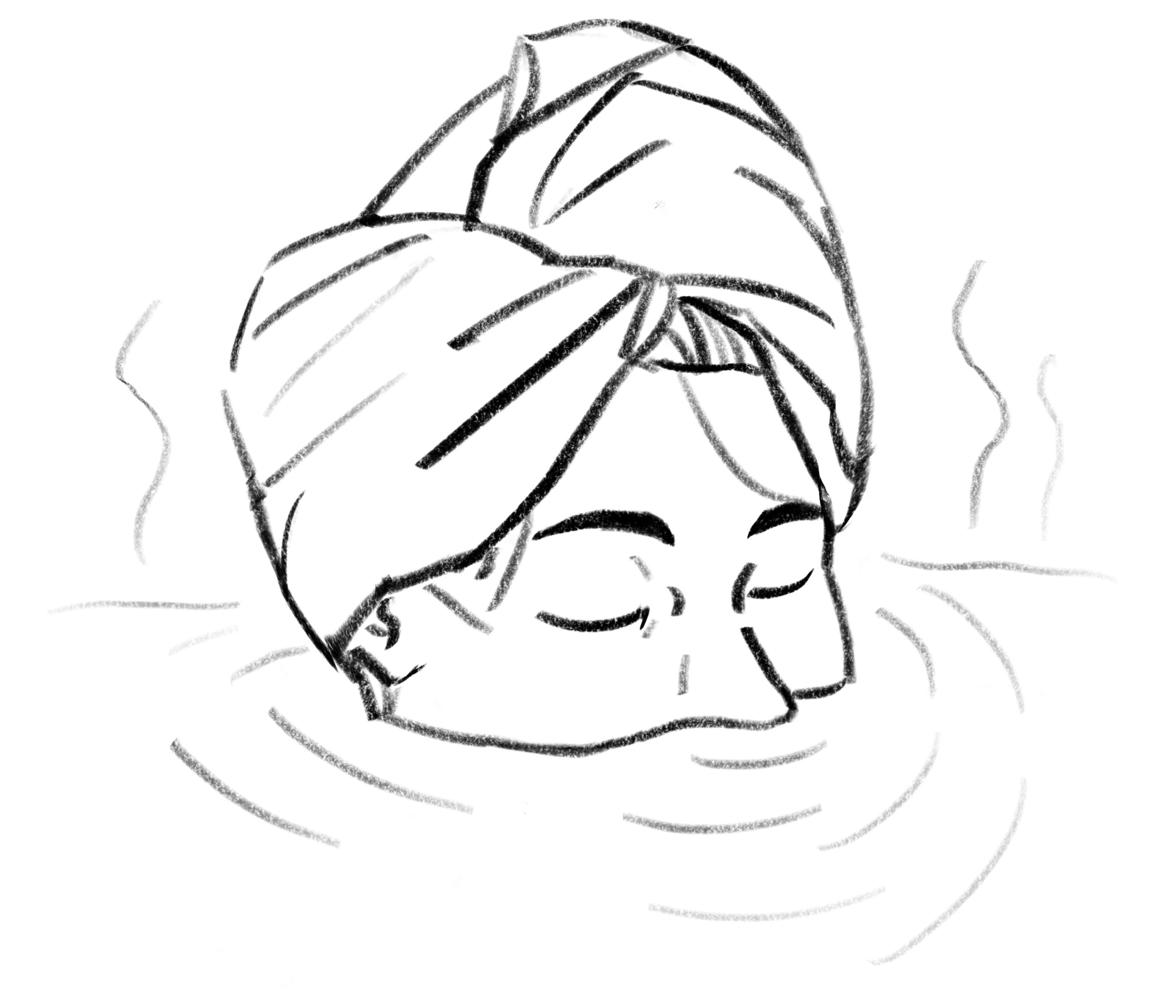

The local “Ohropax” bathhouse had become their refuge, living room, self-care center, pub, and therapeutic practice in one. Named after the iconic brand of German ear plugs, the bath house was shaped like a single earplug; it was essentially a big phallic hammam that was jokingly referred to as “Penisburg”—Penis Castle—by the locals. True to its brand, it was the best insulated bathhouse in town; no sound was able to penetrate the wet walls.

Ilan and Gabriele couldn’t really pinpoint when the first bathhouse had shot up in the Heidelberg area, but it would have been sometime around their high school graduation in 2031. With a four-day work week back then, the time was ripe to claim Friday as a day of immersion. It was a gradual re-routing of energies. Their parents and grandparents had dragged themselves through 60- and 80-hour weeks, executing tasks that now seemed laughable and idiotic.

Entrapped at work and trapped on their devices at home, their parents’ generation of Europeans had experienced a debilitating loneliness. Some governments, such as the United Kingdom’s, had appointed their first minister of loneliness[2] and had launched strategies that highlighted how “loneliness doesn’t discriminate”[3] to counter the evident epidemic. Loneliness nevertheless had persisted and afflicted the mind and heart.[4] Ilan’s and Gabriele’s parents were in a Bowling Alone[5] 2.0 phase at the beginning of the 2030s, a condition amplified by technology that had mastered the process of grasping and monetizing the entire bandwidth of their attention. Robert Putnam’s nightmare had effectively been cast into a never-ending loop of Instagram ad stories.

Few had known how to escape this mirage of desires, and when they did, they simply had no clue what they actually wanted to do with free time not occupied by technology, platforms, or devices. While they debated universal basic income, which answered how they would spend their money in a free-time society, they never really fully answered how to spend free time in a society whose most readily available currency was now free time.

The bathhouse had seemed a logical answer to Gabriele and Ilan back in high school. Throughout human history, communities from all around the world had congregated around bathhouses. The draw was a simple, yet, effective one. Come to this forum, meet those you would otherwise not meet, cleanse yourself, and forget about class, cloth, or clout for a few fleeting hours. The Japanese saw these gatherings as sacred, calling them hadaka no tsukiai or naked communion,[6] while progressive-era New York introduced the bathhouse to uplift the poor by offering sanitary space to all of its citizens.[7] The fascination for coming together in cleansing places was deeply rooted in human history. The practice of bathing was cloaked and steeped in religious and spiritual significance for many cultures, including the Romans, who referred to specific ceremonial baths as salvum lotom[8]. Bathing was effectively humanistic at its very core, appreciated and tested through time.

Society had been glued to its phones, attached via an umbilical cord that was severed only when showering. Bathhouses squarely fell into the category of absolute needs that Keynes saw as “… absolute in the sense that we feel them whatever the situation of our fellow human beings may be …”[9] This innate need for self-care, which in itself is narcissist in nature, was now detached from its digital heroin and replaced with tactile, human and physical presence. Right here, right now, you and me and no devices had become the tagline for Ilan and Gabriele and all those like them back in high school. They would continue this trend throughout their adulthood and in time, a very soft idea would become a very hard law.

While Sarah squabbled with divorcing her friends of their devices, Gabriele had been a well-skilled cheerleader in the early days of the bathhouse revolution. Her arguments were well-crafted, and she sold the voyage to “Ohropax” as a mark of departure from Facebook to a new-found kinship. Gabriele was gifted in that way. It probably stemmed from the fact that she possessed a skill shared by only 300 people in the world. Her craft was so foreign that she constantly needed to describe her motives, skills, and circumstances. In order to be heard and appreciated, she had to mold a narrative that captured the complexity of her being. Once she was able to manage that, the pull factors for a bathhouse had come easy to her.

To take an entire tree trunk and carve a solid fainting chair out of it required many things that Sarah did not have. Sarah was a picture book child of apathy. She could be sedated and aggravated by technology at the same time. As a result, she could never make a definitive case for either in her life. That’s why she needed to morph into Gabriele to do her bidding.

The “Ohropax” bath house had multiple arenas of engagement within it, all soundproof, keeping true to Ohropax’s mantra as the Erfinder der Ruhe, the Inventor of Silence. In the early days, Gabriele would often frequent the “Market Place” within Ohropax. It was a large, elegant octagon of marble that had little fountains of lukewarm water strategically placed in its nooks. Unlike historic hammams, it had the feel of a busy Parisian garden that was drowned and adorned in marble. It was a bustling space, yet it was secluded at the same time, with little pockets of conversation, chess games, and lounging.

Sarah would have loved the slabs of marble, cutouts of geologic history, devoid of any technology. The humming of the 3D fashion printers in Leimen seemed very distant in the hot and humid bath halls. But Sarah never came to the bathhouse. That was Gabriele’s world and stage. As Gabriele had become a bathhouse aficionado, she had moved up to the more specialized rooms within Ohropax. These were thematic and had a social bonus mapped into their layout. One of the rooms was shaped like a Berber hat and barely fit 20 people. It was at most 10 meters in diameter and was set up around a little throne that could be accessed from four little stairways. The stairways were each marked by their compass direction: North, East, South, and West. The room lent itself primarily to literary discussions and was called the Throne. Within the Throne, the idea was that everyone could both verbally and physically elevate their idea and opinion into the room then step down and discuss its merits or shortcomings among those present. Gabriele loved the “Sad Saturday” poetry workshop, which would dissect bleak yet romantic Irish poetry. The sessions were usually intense, as the 90 degree temperature did not lend itself to musing. One had to get to the point or endure the heat of the steam room.

Ilan didn’t particularly enjoy Ohropax, as it felt a bit too busy and universal to him. He went along with Gabriele on occasion, but he much rather preferred the therapeutic bath clubs such as Beijing Baden that had sprung up around the same time as Ohropax did. A communal flyer often advertised some of the various bathhouses in the region.

2040 Bath brands

Beijing Baden

Focused on Reflexology

No device Hammam (NDH)

Similar to a hammam, yet, with a strict no device policy

Ohropax

Guarantees its guests complete quiet and privacy

Kneipe Feucht

Outdoor soaking tub that offers patrons

a relaxing way to enjoy their beers

Detox digital

Centered around therapeutic services provided by trained professional to cleanse oneself of digital addictions

Kathedrale der Sinne

Lends itself from Hindu practices

As early adopters, Ilan and Gabriele had come to know the owners of these private bathhouses very well. In their conversations, they found out that a lot of the bathhouses kept to the unspoken rule of 150. The rule was borrowed from the work of the late Oxford sociologist Robin Dunbar, who, back in the early 2000s, had posited that 150 was the maximum number of individuals with whom any one person can maintain stable relationships.[10] The failure and negative externalities of social media platforms in the 2020’s had reinforced this notion, and bathhouses had been kept intentionally small to reflect the true nature of friendship circles.

Ohropax had taken this approach to heart, as they found that gathering in smaller circles opened up more opportunity for individuals to find the pockets of silence necessary to acquire new information. Just two hours of silence daily could lead to the development of new cells in the hippocampus, a key brain region associated with learning, memory, and emotions.[11] As a result, 4 out of the 10 rooms in Ohropax’s phallic shaped temple of cleansing were quiet zones, like the no-cellphone compartments in trains.

As bathhouses fostered radical self-fulfillment, more and more people became irked by the persistent monetary and commercial barriers. The rich became cleaner, closer to each other, more empathetic through their exchanges with fellow kindred, while the poor showered away on their own, experiencing an understandable fear of missing out and emotional poverty. Ilan had barely been able to afford a monthly pass when bathhouses had first come around in Heidelberg.

The time had been ripe for a manifesto. Bathing should be a human right, much like the right to clean drinking water, Ilan had thought. In due time, petitions were launched. The first one was scraped together by Ilan one night after the second or sixth glass of red wine. Once sober, he edited and uploaded the rough outlines of what would later become the European Right to Unemployment and Meaningful Activity.

Within this expansive legislation was Article 13.2, which required all European counties to setup free communal bathhouses. These communal and public bathhouses needed to cover the four key essential categories agreed upon:

- Relaxation—bathing calms our nerves.

- Community—bathing brings us together.

- Therapy—bathing and touch administered by professionals heals.

- Democracy—bathing is accessible to all. Nobody is obstructed from cleansing him/herself.

In effect, the bathhouse fulfilled the need for a time outside of the time of labor. Secondly, it became mostly resistant to recuperation into the work economy via consumption. Thirdly, the time of “pleasure” was intended first and foremost for the body.

Ultimately, the bathhouse became society’s answer to a form of digitization that left its consumers captive to murky black-box forces that were merely interested in two currencies: attention and money.

The time is zero time

The robes Gabriele made for Ilan wrapped around his wet skin like Greek grape leaves that hugged savory rice. Against the marble, it almost seemed as if the dark grey swirls of marble pulled his grey linen robe into the vortex of its magnificent power. Ilan felt heavy, relaxed and loaded on great ideas. He had just met his neighbors over at the adjacent pool within Ohropax. They had talked about the upcoming block party for the European soccer championships and Gabriele had chimed in with some great bonfire ideas that would make even the most seasoned pyromaniac envious.

Later, with every pressure point that Jacque applied on the soles of his feet, Ilan felt lighter and lighter, until he was convinced that his wet linen robe was levitating over the marble like a camouflaged hovercraft. Jacque would not have been with Ilan on that day in Ohropax if it were not for Gabriele. Back in the early days of the burgeoning bathhouse culture, many therapists such as masseuses, reflexologists, acupuncturists, herbalists, and traditional Chinese medicine specialists had felt unrepresented and unheard in an industry that was diverse in its offerings yet poor in its treatment of its essential staff. At the time, Jacque had barely touched his own feet. Reflexology might as well have been an activewear brand for him. Bored in his day job, which consisted of monitoring the connected factories of the local cement company, he was yearning for a new way to make money, but more importantly a profession that could bring out the best in others.

He had presented this dilemma to Gabriele one night, lying on her bare stomach, his curly hair tickling her diaphragm. As an avid bathhouse visitor, Gabriele had encouraged Jacque to consider a therapeutic profession in one of the many bathhouses that were coming up in the area. Jacque felt insulted. As things stood, he could not match Gabriele’s beauty, and now he had to demote and degrade himself even further by pressing people’s feet? He might as well have been working in a Roman fullonica[12] handling the urine of the masses.

Economic factors years later would convince Jacque to become a registered therapist, however, it was the emotional promise of his new work that ultimately broke his stubborn resistance. Jacque, with friends like Gabriele and Ilan, came to view bathing for what it was for many people, namely:

- A prelude to quality conversation.

- A prelude to attraction and romantic intimacy.

- A prelude to forgetting the pains and violence of our world and instead replacing these with clean and calm environments.

- A prelude to embracing narcissism in its natural form, stripping it of its digital interface, and letting people turn narcissism into something less mediatable.

The last point was of special interest to Jacque, who, through his work, came to embrace the concept of recycling narcissism. Taking the negative externalities of digital narcissism and holding a mirror up to its absurdness. The time was ripe for his work to bear fruit. Europe was a bathhouse continent now by law; the Middle East and Asia were re-discovering their historic bathhouse roots and North America and other continents would hopefully follow soon. Those who worked in bathhouses were now elevated in prestige with the new law in force. Becoming an acupuncturist was now a viable career track, reserved exclusively for humans. Body to body work remained one of the few areas untouched by automated hands. The bathhouse was made by humans for humans. An existential arena if you will, where people could choose their own values and make themselves.

“Thank you Jacque! That was blissful as always. Let me get dry and dressed and we will meet you out back in 30 minutes, ok?” Ilan gestured to Gabriele, who was roaming the bathhouse like a bloodhound out for good conversations. They both decided to head out and freshen up before Jacque’s big exhibition opening. Through his work at the bathhouse, Jacque had come to observe all kinds of bodies. Faced with this kaleidoscope of beings, he realized how tragic and corrupt our historic visual narratives were. As he would replay his day at home, he would often scroll through an Instagram archive he kept. When he struck gold, he would print out an Instagram picture of interest and lay it down on the right side of his wide oak table. On the left, he would then lay out a blank sheet of paper and sketch out a similar body, silhouette, or body part from memory. Initially one saggy breast on the left would meet a perfectly cupped and luscious Instagram breast on the right. Soon, Jacques couldn’t stop contrasting the real life of the bathhouse with the silo of artificial Instagram history.

That night, while holding two glasses of Merlot at the opening, Ilan looked over Jacque’s work, mesmerized by the bland and instant kitsch he could now discern and distinguish, like a sommelier who had been trained in body positivity and spotting bullshit. Proud of his new skills, he turned around to look for Gabriele to offload one of the two wine glasses. For the life of him, he could not spot the her long wavy hair. He kept pacing around the studio like a caged animal but could not spot his bathing confidant. Instead, he spotted Sarah across the room. He walked up to her and noticed her wet hair. Curious, he asked her about it. She admitted to him that she had just literally taken the plunge and had ventured out into the new public Badehaus Heidelberg for the first time ever. And with that literal plunge, Sarah had overcome her inhibition, tech sedation, and social aversion and opened herself up to socializing and interacting with others. The visit to the bathhouse had married the split personalities she had inhabited for so long. Sarah and Gabriele were now one, an omega bond of charisma, confidence and candor. Together they proclaimed:

“We are in the year 2040. The bathhouse is a constitutional right for us humans, speaking to our newly acquired free time, which transcends the historical notion of time as productivity. The time of the now is zero time, that is, the negation of the real time of production. We are free. We are clean. We are all enjoying revolutionary play. Everyone is a narcissist together.”

Footnotes

1Keynes, John Maynard. 2010. “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.” In Essays in Persuasion, edited by John Maynard Keynes, 321–32. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-59072-8_25. [back to text]

2 Prime Minister’s Office, Office for Civil Society, and The Rt Hon Theresa May MP. 2018. “PM Commits to Government-Wide Drive to Tackle Loneliness.” GOV.UK. January 17, 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-commits-to-government-wide-drive-to-tackle-loneliness. [back to text]

3 Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Office for Civil Society, Prime Minister’s Office, Tracey Crouch MP, and The Rt Hon Jeremy Wright QC MP. 2018. “A Connected Society: A Strategy for Tackling Loneliness.” GOV.UK. October 15, 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/750909/6.4882_DCMS_Loneliness_Strategy_web_Update.pdf. [back to text]

4 Valtorta, Nicole K., Mona Kanaan, Simon Gilbody, Sara Ronzi, and Barbara Hanratty. 2016. “Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Observational Studies.” Heart 102, no. 13: 1009–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790. [back to text]

5 Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community is a 2000 nonfiction book by political scientist Robert Putnam. In it he surveys the decline of social capital in the United States. He describes among others the reduction in all the forms of in-person social interactions upon which Americans used to found, educate, and enrich the fabric of their social lives. Bowling features as a prominent example and metaphor in this case. Hence, the title bowling alone. [back to text]

6 Macfarlane, Alan. 2008. Japan Through the Looking Glass. London: Profile Books. p. 35. [back to text]

7 Renner, Andrea. 2008. “A Nation That Bathes Together: New York City’s Progressive Era Public Baths.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 67, no. 4: 504–31. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2008.67.4.504. [back to text]

8 Bruun, Christer. 1993. “Lotores: Roman Bath-Attendants.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 98: 222 – 28. [back to text]

9 Kant, Shashi, and Albert R. Berry, eds. 2005. Economics, Sustainability, and Natural Resources. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 42. [back to text]

10 Sutcliffe, Alistair G., Jens F. Binder, and Robin I. M. Dunbar. 2018. “Activity in Social Media and Intimacy in Social Relationships.” Computers in Human Behavior 85 (August): 227–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.050. [back to text]

11 Kirste, Imke, Zeina Nicola, Golo Kronenberg, Tara L. Walker, Robert C. Liu, and Gerd Kempermann. 2015. “Is Silence Golden? Effects of Auditory Stimuli and Their Absence on Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis.” Brain Structure and Function 220, no. 2: 1221–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-013-0679-3. [back to text]

12 The Roman equivalent of a laundromat that used urine collected on the streets to wash and cleanse clothing items, as well as soften leather products. Wilson, Andrew. 2003. “TheArchaeology of the Roman Fullonica.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 16: 442–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759400013258. [back to text]

Discussion questions

How can we stop the monetization of our attention and instead foster interpersonal relations?

Why did societies stop going to bathhouses? Are we missing out of something?

What are the greatest barriers to encouraging mass attendance of bathhouses?

Further Reading

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Office for Civil Society, Prime Minister’s Office, Tracey Crouch MP, and The Rt Hon Jeremy Wright QC MP. 2018. “A Connected Society: A Strategy for Tackling Loneliness.” GOV.UK. October 15, 2018. ➚

Emerging Technology from the arXiv. 2019. “Your Brain Limits You to Just Five BFFs.” MIT Technology Review. ➚

Klinenberg, Eric. 2018. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. New York: Crown.

Renner, Andrea. 2008. “A Nation That Bathes Together: New York City’s Progressive Era Public Baths.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 67 no.4: 504–31. ➚

Sutcliffe, Alistair G., Jens F. Binder, and Robin I. M. Dunbar. 2018. “Activity in Social Media and Intimacy in Social Relationships.” Computers in Human Behavior 85 (August): 227–35. ➚

In Mangal’s New World

Mangal’s mutiny against the machine was driven by the historical injustices it reminded him of. His rebellion ushers in a long lasting socio-technical revolution that changes the way people live in 2040.

Living in Togedera

Do you ever imagine a society where care homes for older people have become obsolete—where senior citizens who need round-the-clock care can stay at home?